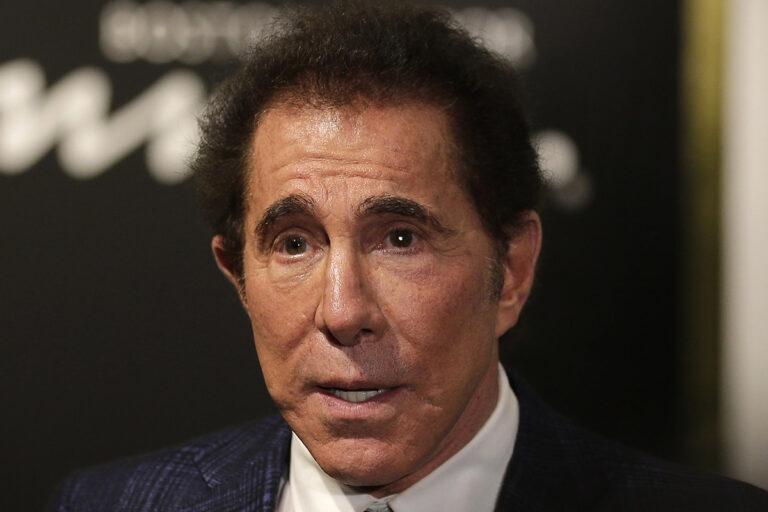

Last week, U.S. District Court Judge James Boasberg dismissed a years-long effort by the Justice Department to force former casino owner Steve Wynn to register as a foreign agent. He did so despite agreeing with aspects of the DOJ’s case and expressing discomfort with his own ruling.

For Wynn, the dismissal surely comes as a relief. It probably marks the end of the DOJ’s attempts to penalize him for his involvement in negotiations between the Chinese government and the Trump administration. However, the former Wynn Resorts CEO will continue to fight legal battles on other fronts.

The story, which Bonus has previously covered in detail, begins back in May 2017. That’s when China’s efforts to enlist Wynn as an agent of the Chinese government ensued in a meeting that, as Boasberg put it, “included an unusual cast of characters.”

An Unusual Cast of Characters

These characters included former Republican National Committee finance chair Elliott Broidy, businessperson Nickie Lum Davis, and Prakazrel Michel.

Michel is better known as Pras, a former member of the hit 1990s hip-hop group The Fugees. This led to Boasberg citing Fugees’ lyrics at multiple points in his ruling. For example:

Perhaps embracing The Fugees’ famous line—‘ready or not, here I come, you can’t hide,’—the PRC sought to have the Trump Administration cancel the visa of and remove from the United States an unnamed Chinese businessperson whom the PRC had charged with corruption. The Chinese businessperson, perhaps understanding that ‘jail bars ain’t golden gates,’ had fled China in 2014, seeking political asylum in the United States.

What is a “Foreign Agent”?

The DOJ first advised Wynn to register as a foreign agent a year after the Chinese lobbying campaign began. That first warning gave Wynn 30 days to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) as an agent of Chinese Vice Minister for Public Security Sun Lijun.

Wynn, through counsel, disputed the DOJ order. He argued that he did not meet the statutory definition to be considered an “agent” of either Sun or the People’s Republic of China (PRC). He also insisted that none of his actions was taken “in the interests” of Sun or the PRC.

Over the next four years, the DOJ and Wynn exchanged numerous letters. The Justice Department continued to insist that he was obligated to register under FARA. It also noted that its “further investigation into the matter had [only] strengthened” this conclusion.

Finally, on April 13, 2022, the DOJ issued a second 30-day ultimatum. When Wynn failed to comply, the Attorney General filed suit, seeking a permanent injunction under FARA.

The Defense Celebrates

Wynn’s lawyers, Reid Weingarten and Robert Luskin, praised Boasberg’s ruling. They issued a statement saying:

We are delighted that the District Court today dismissed the government’s ill-conceived lawsuit against Steve Wynn. Mr. Wynn never acted as an agent of the Chinese government and never lobbied on its behalf. This is a claim that should never have been filed, and the Court agreed.

Boasberg seemed to find some of the evidence against Wynn quite compelling. In his ruling, he outlined the timeline of Wynn’s involvement in US-China affairs:

Around this same time, Defendant’s casino business in Macau, a special administrative region of the PRC, also entered the conversation. According to the Complaint, Wynn’s lobbying campaign—which was sandwiched between a 2016 decision by the Macau government to significantly limit the number of gaming tables at his casino and an upcoming license renegotiation for those same casinos in 2019—was motivated all along ‘by his desire to protect his business interests in the PRC.’

By October 2017, when it became evident that the PRC’s lobbying campaign had failed to elicit the removal of the PRC national and that Wynn could do no more to help, he ‘gracefully’ exited his role as agent.

No Choice but to Dismiss

Despite his misgivings, however, Boasberg ruled in favor of Wynn. He felt he had no choice but to do so, based on the precedent set in another case, United States v. McGoff.

In that case, Wynn’s defense argued, the court found that FARA’s five-year statute of limitations applies from the last day the person was actively engaged as a foreign agent. Since, by October 2017, Wynn had disinvolved himself with the lobbying campaign, Boasberg agreed with the defense that the government had waited too long to pursue the case and that dismissal was his only option.

He wrote:

Indeed, the Court does not dispute that even agents who have since ended their agency relationship but who never registered their activities are still in possession of “information that [FARA] says the public needs. . . . [And] While the goals of FARA are laudable, this Court is bound to apply the statute as interpreted by the D.C. Circuit. And that requires dismissal.

The Justice Department still has the option to appeal to the D.C. Circuit. However, the appeals court would likely make the same ruling based on that precedent. It may be that this marks the end of the case against Wynn.

The statement released by the DOJ after the ruling was non-committal in that regard:

While the court considered itself bound to apply an earlier precedent of the DC Circuit notwithstanding these concerns, the government respectfully disagrees with today’s ruling and is considering options in the litigation and more generally.